She went by the name of Milicent Patrick, appeared in 21 motion pictures over a span of 20 years (1948 to 1968), acted in dozens of television shows, worked as a costumer, character designer, and illustrator on countless other films, and took a significant role in creating the SF cinema’s most distinctive character of the 1950s, yet today she is a mystery woman in the most literal sense of the term.

Her real name is (or was) Mildred Elizabeth Fulvia di Rossi and, according to some sources, she was born an Italian baroness—the Baronesa di Polombara. She was/is a multi-talented, statuesque beauty who, remarkably, shied away from the limelight, and received screen credit for only a relative handful of the many pictures she worked on, both in front of and behind the cameras. The Screen Actors Guild currently lists her among the missing, and no definitive record of her life, her death, or her whereabouts seems to exist beyond the early 1980s.

She was the daughter of Camille Charles Rossi, an architect and engineer who oversaw the construction of William Randolph Hearst’s Castle estate in San Simeon, California. Accordingly, Ms. Patrick spent her youth in San Simeon and in South America accompanying her father on his various construction assignments. It is believed that she was born around 1930. Musically gifted, she had early ambitions of becoming a concert pianist, but instead studied art on a scholarship after she graduated from high school at the young age of 14. She attended the Chouinard Institute in California, and was subsequently hired by Disney to work on animated films in the late 1940s. Her resumé claims the distinction of her being the first female animator ever hired by that famous studio.

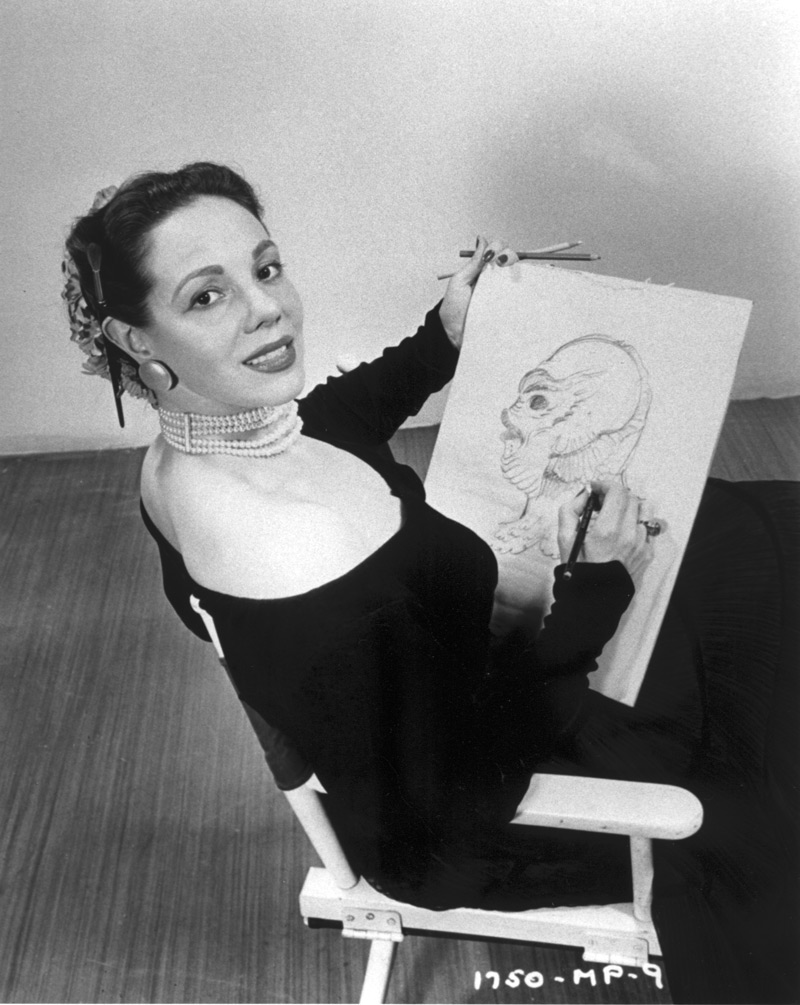

In early 1954 she went on tour to promote the March release of the 3-D film Creature from the Black Lagoon. By all early accounts it was a production for which she performed a key role in developing the costume for its title character. In the century-long history of SF films, save for King Kong and Godzilla, there is perhaps no better-known entity than the Creature—nor one more emblematic of both 1950s SF cinema or of the 3-D motion picture process.

Even before Ms. Patrick began her tour, make-up department head George Hamilton “Bud” Westmore had sent memos to the Universal front office taking exception to the studio’s intention to bill her as “The Beauty Who Created the Beast,” by claiming that the Creature was entirely the product of his own efforts. In February, while the tour was in full swing, Westmore went to great lengths to secure clippings of her numerous newspaper interviews, some citing her as the Creature’s sole creator, without mention of Westmore or of the other members of the make-up department staff. Westmore made it clear in his complaints to Universal executives that he had no intentions of engaging Ms. Patrick’s services as a sketch artist again. In correspondence between executives Clark Ramsey and Charles Simonelli dated the first of March 1954, Ramsey noted that Westmore was behaving childishly over the matter, and that Patrick had done everything possible to credit Westmore during her interviews. He further expressed regret at Westmore’s intention to penalize her. True to his threat, however, Westmore stopped using her after she completed drawings for Douglas Sirk’s Captain Lightfoot, released by the studio the following year.

Her exile from the Universal make-up department brought an end to a promising aspect of her career, and forever clouded the details of her efforts while on Westmore’s staff. During that time, the studio produced their most notable creations of the ’50s science fiction boom, but just precisely what her contributions may have been to those films has been largely muddled since Westmore’s tirade. According to magazine articles and newspaper accounts that predate the Westmore flap, Milicent Patrick designed the Xenomorph for It Came from Outer Space (1953), the Gill Man (Creature from the Black Lagoon ), the Metaluna mutant for This Island Earth (1954), and was a mask maker on Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953) and The Mole People (1956); a glut of ghastly creations with which any self-respecting monster maker would be proud to be associated.

Universal had made its mark, and a considerable amount of money along the way, as the American film industry’s principal supplier of horror movies during the 1930s and ’40s. During those years, this kind of fanciful escapism seemed to offer comfort to those suffering through the global depression and, later, through the grim realities of the Second World War; but by war’s end the production of such films dropped off sharply. With the ending of hostilities came both optimism and anxiety about the new era that was to emerge from the ashes of that great global conflict. Science suddenly seemed to be a new force that touched the lives of everyone, but it was also a double-edged sword, possessing the power both to enrich and to destroy.

Early in the 1950s producers like Howard Hawks and George Pal had proven quite conclusively that fantastic ideas, supported by the rationales of science rather than superstition, had great credibility with moviegoers in the new Atomic Age, and could pack movie houses with eager patrons. Their efforts inspired dozens of similar productions all across the economic spectrum, from big-budgeted undertakings by the major studios, to shoe-string productions by small independents. Often the distinctions between science and the supernatural were blurred, or were simply ignored.

By 1953 a veritable tidal wave of SF movies, or something very much like them, descended on neighborhood theaters. Early in the 1950s the newly reorganized studio, now renamed Universal-International, made its bid to capture the lead in the making of science fiction pictures. SF seemed the logical modern extension of the horror film, and it operated on many of the same dramatic principles. Thus, U-I’s early efforts in the genre were often thinly disguised monster movies with implausible scientific ideas to support them. Indeed, in seemingly assembly-line fashion, the creatures frequently came out of Westmore’s make-up department before the scripts were even written. Still, the studio’s output of quality category films from this period reads today like a checklist of widely celebrated genre classics.

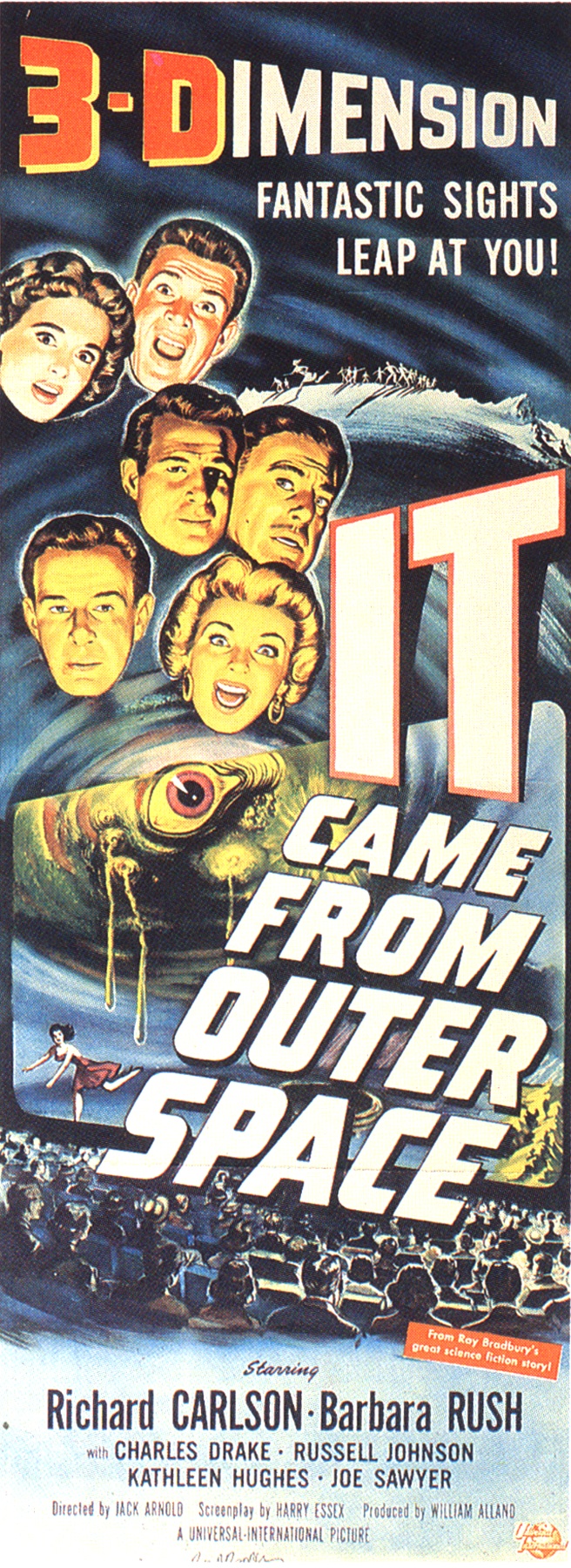

U-I’s first significant venture into SF was also one of the first 3-D films to be undertaken by a major Hollywood studio. Of all the majors, only Warner Bros.—with House of Wax (1953), its color re-make of The Mystery of the Wax Museum (originally filmed in 1933 in an experimental two-strip Technicolor process)—had been as quick as U-I to take the plunge into making stereoscopic pictures. Prompted by their success, MGM, Paramount, and Columbia soon followed. Until that time, 3-D had been purely the domain of the more enterprising independents, and these early films had little more to offer than low-cost gimmicks that hurled objects at the screen. But the new process had captured the imagination of the movie-going public, and what better vehicle (seemingly so futuristic by its very nature) was there to present SF stories than in this startling process that mimicked the look of the three-dimensional universe? At its height, in the early 1950s, the 3-D process seemed such a watershed of innovation that most studios seriously considered if they’d ever be able to find rental outlets for the large backlogs of “flat” films that filled their vaults.

Universal’s first SF picture, It Came from Outer Space, was not just any ordinary story by any ordinary author; it was instead based on a compelling treatment about aliens that could mimic human appearance (thus echoing the anxieties of the McCarthy era, then at its height), and was written by none other than America’s top science fiction writer of the day, Ray Bradbury (b. 1920). By early September 1952, when Bradbury sat down at his typewriter to create the first of his five drafts of the treatment, he’d already made his mark with his popular story collections The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951), and was nearing completion of Fahrenheit 451 (1953), a novel about a future in which books are systematically burned.

Universal’s first SF picture, It Came from Outer Space, was not just any ordinary story by any ordinary author; it was instead based on a compelling treatment about aliens that could mimic human appearance (thus echoing the anxieties of the McCarthy era, then at its height), and was written by none other than America’s top science fiction writer of the day, Ray Bradbury (b. 1920). By early September 1952, when Bradbury sat down at his typewriter to create the first of his five drafts of the treatment, he’d already made his mark with his popular story collections The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951), and was nearing completion of Fahrenheit 451 (1953), a novel about a future in which books are systematically burned.

From the outset, and through the first few drafts, the property was curiously entitled Atomic Monster. Most likely this moniker came from the studio and not from Bradbury, who recalls that the working title of the treatment was The Meteor. In the end, although Harry Essex wrote the final screenplay essentially by just retyping and slightly expanding Bradbury’s final draft of the treatment, It Came from Outer Space became a milestone in the genre. In addition to being Universal’s first real SF picture, and its first 3-D film, it was also shot in a 1-to-1.85 (height to width) aspect ratio, making it an early wide screen movie. The following year, 1954, would see the release of the first practical, truly anamorphic wide screen pictures in CinemaScope and similar processes; usually with aspect ratios in excess of 1-to-2. It Came from Outer Space was also recorded in stereophonic sound, and in some screenings during its premiere, foam rubber boulders were dropped onto the first few rows of seats during an avalanche shown in the film’s opening minutes. The film was also director Jack Arnold’s maiden voyage in the science fiction genre, quickly establishing him as an SF specialist of the first magnitude.

It Came from Outer Space tells the story of science writer and amateur astronomer John Putnam (Richard Carlson), and his fiancée, Ellen Fields (Barbara Rush), who witness the landing of a meteor in a desolate region of the desert beyond the town of Sand Rock, Arizona. When Pete Davis (Dave Willock), a helicopter pilot, flies them out to the crash site, they discover an immense crater into which Putnam descends alone. There, in the steaming depths of the crater, Putnam briefly glimpses a huge spherical ship, and sees something ominous moving about in the darkness of the ship’s interior. When the ship’s heavy door swings shut, the sound initiates a rockslide that completely conceals the vessel under tons of fallen debris. No one but Ellen will believe Putnam’s fantastic claims of intelligent visitors from outer space.

As the days pass, members of the community disappear: first, two linemen for the telephone company, Frank (Joe Sawyer) and George (Russell Johnson), who are working out on the desert alone; then an astronomer, Dr. Snell (George Eldredge) and his assistant (Brad Jackson). The missing persons are replaced by suspiciously behaving surrogates who are actually shape-shifting aliens. Putnam eventually learns that the aliens have accidentally landed on Earth and wish only to repair their ship and leave. Once disguised as ordinary people, they can presumably pass freely among the residents of Sand Rock as they go about securing the materials they need to repair their craft. Putnam advocates holding back on any action that might be taken against the aliens when Sheriff Matt Warren (Charles Drake) finally accepts the truth of Putnam’s claim, but the continued abduction of members of the community, to include Ellen, brings an angry mob out to the crater. Before the mob arrives, Putnam makes his way to the ship and persuades the aliens to release their human captives as a gesture of good will. As the townspeople gather at a nearby mine shaft that adjoins the crater, Putnam uses dynamite to seal off the mine, thus affording the aliens time to complete their preparations for departure. Soon after, the ground begins to quake, and the ship breaks through the tons of rubble to rise into the night sky and veer off into black infinity. As the craft disappears, Ellen asks Putnam whether or not the creatures have gone for good. He responds philosophically, “No, just for now. It wasn’t time for us to meet. But there’ll be other nights, and other stars to watch. They’ll be back.”

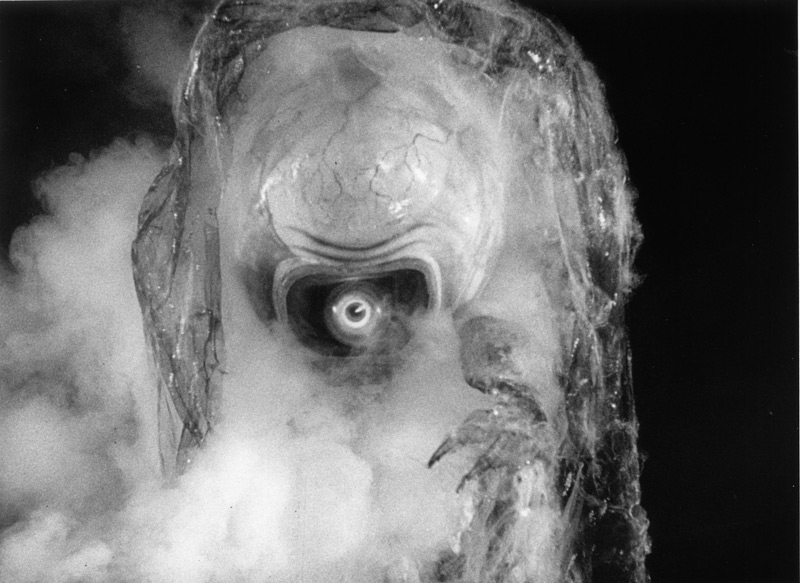

Through the early drafts of Bradbury’s treatment, the visitors are described as lizard-like in appearance. Having set the objective of their being truly repulsive and terrifying by human standards, Bradbury seems to have concluded that lizards might not do. In the last of his treatments he appears to have abandoned the lizard concept almost entirely in favor of something more nebulous. The ambiguities of his description, however, oddly approximate what finally made it onto the screen. He says that we glimpse only the merest suggestion of something out of a nightmare, “something which suggests a spider, a lizard, a web blowing in the wind, a milk-white something dark and terrible, something like a jellyfish, something that glistens softly, like a snake.”

Harry Essex’s final script, entitled The Visitors from Outer Space, offers little more by way of definition for these beings. His exasperating comment during the scene at the mine shaft entrance—when Putnam finally comes face-to-face with one of the creatures—is that an exact description of “the horrible creature, enveloped in smoke,” will be provided. None, of course, ever was—at least not on the written page.

Early in the pre-production stages of It Came from Outer Space, Bud Westmore’s make-up department was presented with the difficult task of translating the alien’s description (or lack of one) into something that could be photographed and captured on screen. Art directors Bernard Herzbun and Robert Boyle seem to have concentrated their efforts mainly on constructing an impressive recreation of the Arizona desert on Universal’s soundstage. Presumably, Milicent Patrick was then an active participant in the make-up department, worked directly on the creation of concept sketches for the creatures—or so some documents predating the 1954 flap with Westmore indicate. In the meantime, the promotional department seized on the idea of using a giant eye to represent the creatures in the film’s advertising graphics.

Early make-up department sketches show a large-domed being, first with two eyes, then, finally, with one in the center of its head; its body merely suggested and largely amorphous, with only a hint of appendages that approximate arms. Some of the early discarded designs (probably suggested by Edd Cartier’s illustrations for the SF anthology Travelers of Space; Gnome Press, 1951), were later used in other U-I films—most notably for the Metaluna mutants in This Island Earth (1955). It Came from Outer Space proved to be the biggest box office success of the summer of 1953, due mainly to its adept use of the 3-D process and to its novel storyline.

In December 1952, long before the cameras started rolling on It Came from Outer Space, the film’s producer, William Alland, submitted a screen treatment by Maurice Zimm to the U-I front office for consideration; its title was Black Lagoon. Also slated for production in 3-D, the idea for this new film grew out of a dinner conversation that Alland had a decade earlier with Latin American filmmaker Gabriel Figueroa at the home of actor/director Orson Welles, during the filming of Citizen Kane at RKO, sometime in 1941. Alland, then an actor, had been a member of Welles’s critically acclaimed Mercury Theater radio company—the same dramatic ensemble that had triggered a national panic with its broadcast of The War of the Worlds on October 30, 1938. Alland also had the small but pivotal role of the largely unseen Thompson in Citizen Kane, the inquisitive newspaperman who seeks to unravel the mystery of Rosebud. In a memo written in early October 1952, Alland recounted Welles’s dinner party and the fantastic story he’d heard of a race of creatures—half man, half fish—that purportedly lived in a remote region along the Amazon River. Maintaining that his story was true, Figueroa further claimed to have financed an expedition to the location in search of the creatures.

Alland and the film’s director, Jack Arnold, had critical input in the early development of the creature’s appearance. In both Alland’s memo and in his directions to Zimm, certain physical characteristics of the creature were outlined. As Jack Arnold recounted in a 1975 interview, “One day I was looking at the certificate I received when I was nominated for an Academy Award [for the 1950 documentary, With These Hands ]. There was a picture of the Oscar statuette on it. I said, ‘If we put a gilled head on it, plus fins and scales, that would look pretty much like the kind of creature we’re trying to get.'” Arnold, who possessed some modicum of artistic talent, produced a rough sketch that was passed along to Bud Westmore and his associate, Jack Kevan, in the Universal make-up department. Arnold’s drawing was then handed over to Milicent Patrick for refinement.

Differing published accounts of the development of the Gill Man costume set the price tag at between $12,000 and $18,000 (in 1953 dollars—roughly what was then the equivalent in cost of a fairly spacious home) and its gestation time at between six to eight and a half months. Whatever the true numbers may have been, it also took great talent and imagination to develop this indelible cinematic icon. Other key players on the Westmore make-up team were Jack Kevan, Westmore’s closest associate and a gifted make-up artist and laboratory technician with some 20 years of experience in his craft at the time, and sculptor Chris Mueller. Mueller was principally responsible for sculpting the various Creature heads as well as other important sections of the costume, and in the same year oversaw the creation of the giant squid and the interior of the Nautilusfor Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea . The Disney film went on to win the 1954 Academy Awards for special effects and art direction. Mueller also sculpted the details of the Temple of the Goddess of Light for the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad.

In order to produce the Gill Man costumes, a body cast was made of Ricou Browning, the actor hired to portray the character in the underwater scenes. The unusual swimming technique Browning devised for the Creature is graceful and, at the same time, suggestive of something not entirely human. The 6′ 4″ Ben Chapman, a nightclub performer, was engaged to play the character on land, presumably because of his height and agility. In full costume, Chapman stood approximately 6′ 7″, whereas Browning was somewhat under six feet. Plaster of Paris body castings of Browning and Chapman were used to produce custom, formfitting latex leotards onto which foam rubber parts of the Gill Man were glued. The basic sculpting of the body details was done on a whole body cast of Browning, and the foam rubber pieces were later modified to fit the taller Chapman. One difference, an extra row of scales across the chest of Chapman’s costume—to allow for the difference in girth between the two actors—is one of the few tell-tale signs as to which actor appears on screen in any given scene.

The heads, hands, and feet of the Gill Man were sculpted separately in clay, then cast in plaster. The first experimental heads were sculpted over a bust of actress Ann Sheridan, supposedly because it was the only life mask in the Universal make-up department with a neck, and it was especially important to producer William Alland that the gills on the Creature’s throat be seen to expand and contract on screen (an effect achieved by the use of an expandable bladder operated by technicians off camera). The plaster molds were then filled with whipped foam rubber and baked in an oven. The remainder of the Gill Man’s body was sculpted in manageable sections over a more durable stone cast of Browning, and similarly formed in foam rubber. Initially, the foam rubber pieces were mounted on the leotard while Browning was wearing it, but the intense heat produced as the adhesive cured, and the risk of chemical burns, prompted the making of an additional body cast to provide rigid support while the costumes were being assembled.

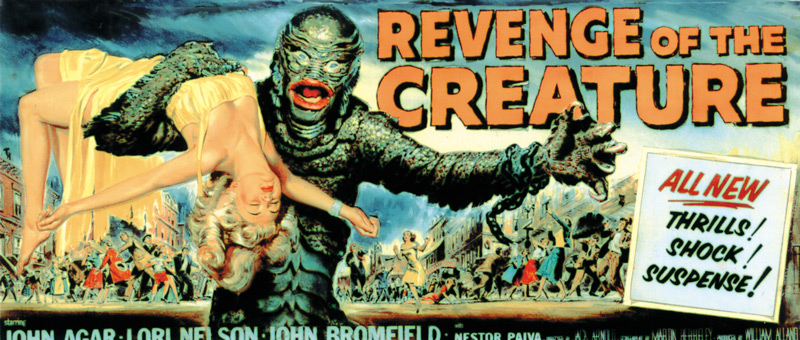

The title “Black Lagoon” stayed with the production until the film’s previews in the fall of 1953, when it went into general release as Creature from the Black Lagoon. The flamboyant title, the innovative costume, and the expert use of 3-D underwater photography quickly placed the character in the pantheon of the most popular movie monsters of all time, and identified it as an icon of the 3-D process. The costume is almost certainly the crowning achievement of Bud Westmore’s film career. Although the design of the Gill Man was novel and quite ingenious, the plot was hardly new. It owes much to earlier “lost world” films, and especially to the 1933 King Kong. This becomes particularly apparent when considered with the film’s first sequel, Revenge of the Creature (1955).

The film opens in the jungle wilderness surrounding a remote tributary of the Amazon River. There Dr. Carl Maia (Antonio Moreno) and his native helpers, Luis (Rodd Redwing) and Tomas (Julio Lopez) uncover a peculiar fossil—the webbed hand of a creature that strongly suggests a direct link between humankind and the sea. Maia, armed with a photograph of his remarkable find, returns to the Instituto de Biología Maritíma in Brazil to discuss the possibilities of sponsorship for an expedition to find the rest of the fossil. There he encounters visiting American scientists from an aquarium in California: Dr. David Reed (Richard Carlson), a former student of Maia’s, and his girlfriend, Kay Lawrence (Julia Adams). At a later gathering in California with Reed’s boss, the ambitious Mark Williams (Richard Denning), plans are quickly drawn to outfit the expedition. The research team, which includes Reed, Williams, Maia, Kay, and Dr. Edwin Thompson (Whit Bissell), makes its way along the Amazon River in an old fishing boat, named the Rita, with her crew—Lucas (Nestor Paiva), its captain, and the Indian brothers Zee (Bernie Gozier) and Chico (Henry Escalante).

The group arrives at Maia’s campsite to find the bodies of Luis and Tomas horribly mutilated in an animal attack. Unbeknownst to them, a living specimen of Maia’s man-fish has assaulted and killed the human intruders. Alarmed, but undaunted, they proceed to search the area for additional remains of the fossil, but to no avail. They deduce that some of the sediment bearing the fossil might have broken away and been carried downstream to the mysterious Black Lagoon. Lucas warns that no one has ever lived to return from the lagoon. Boldly, they venture forth.

With the Rita now anchored at the lagoon, Kay decides to go for a swim. While in the water she is observed unseen, and is curiously stalked by a strange aquatic creature that mimics her movements. When she returns to the ship, something snags in a fishing net, which is pulled up to reveal a huge tear, and a dagger-like fingernail caught in the webbing that resembles the powerful claws of Maia’s fossil. Soon after, David and Mark encounter the man-fish while submerged in the lagoon gathering geological samples. Mark fires a barb from his spear gun and, wounded by it, the strange creature swims away. Later it climbs aboard the Ritato exact vengeance and drags Chico to his death. Convinced that its capture would be the archeological find of the century, Mark ignores the risks and pressures the others to go after it. They eventually subdue the beast by lacing the water with a native drug called Rotonone. The Creature is anesthetized but manages to kill Zee in the process of being captured. The animal is kept onboard in a tank that’s secured with a bamboo barrier but, as it awakens, it breaks free badly wounding Dr. Thompson and getting burned by a lantern during its escape. Mark, despite the number of deaths, refuses to relent in the effort to capture the animal alive. In an underwater struggle with the man-fish, Mark is finally killed.

As the few survivors attempt to flee the lagoon they find their exit route blocked with tree branches and other debris. The creature, being highly intelligent, has laid a trap preventing their escape. Armed with an oxygen bottle filled with Rotonone, David attempts to wrap a cable around the debris to pull it out of the way with the ship’s winch. The barrier, however, is a ploy. Obsessed with Kay, the man-fish climbs onto the Rita and kidnaps her. David follows them to the Creature’s grotto, where he finds Kay unconscious lying on an altar-like slab of rock. As David embraces her, the Creature rises up out of a nearby pool in the mist-shrouded grotto and attacks him. Armed with only a knife, David’s weapon seems ineffectual against the armored scales of the raging beast. Lucas and Dr. Maia arrive in the nick of time and begin firing their rifles at the monster. It flees into the jungle badly wounded and staggers off into the water where it sinks below the waves, presumably to die.

Although still photographers and filmmakers experimented with duplicating the appearance of the three-dimensional world for decades, the various means of achieving that illusion remained little more than quaint curiosities. On Thanksgiving Day 1952, that all changed, however briefly, with the premiere of Arch Oboler’s independently produced motion picture, Bwana Devil . Its unprecedented success could not have been better timed. Movie house attendance had fallen off sharply with the coming of television and exhibitors were desperate for new ways to bring patrons back into their theaters.

While the studios enjoyed the hearty profits derived from the new process, in a very short time movie patrons began complaining of eyestrain and headaches. The causes of these problems were numerous and, by the summer of 1953, wild speculation over the potential hazards of watching 3-D movies prompted a full-blown health scare. Although the health concerns were many, they were also potentially correctable. Patrons also complained about the necessity of wearing the special polarized glasses—particularly if they already wore corrective lenses.

To address these problems, Universal-International exhibited Creature from the Black Lagoon using an entirely new system, called Moropticon, that seemed to correct all of 3-D’s inherent flaws, except, of course, for the need to wear the polarized glasses. Creature was the first feature-length movie to utilize a single-strip 3-D film system.

As with It Came from Outer Space a year earlier, Creature from the Black Lagoon was wildly successful, and almost immediately Alland began planning a sequel, Revenge of the Creature (1955). This installment would bring the Gill Man out of the primordial jungle and would set him lose in the city streets. Jack Arnold was again signed to direct. Although critics seemed unanimous in their loathing of the film, movie audiences couldn’t seem to get enough of the love-smitten man-fish. However, by late summer of 1954, the negative effects of the health scare had left an impression on the movie-going public that could not be dispelled, no matter what remedial steps the film studios were willing to take. Revenge was to be the very last 3-D feature-length film of the 1950s.

Rounding out the relatively thin storyline of Revenge of the Creature is a minimal subplot about a friendly competition between Joe Hayes (John Bromfield), one of the Creature’s captors, and a college professor, Clete Ferguson (John Agar), who vie for the affections of graduate student Helen Dobson (Lori Nelson). The pretty, blonde-haired Dobson is an ichthyology major, and is also the subject of the Gill Man’s intense and sometimes reckless interest, as Kay Lawrence had been in the previous film. There is also a brief appearance by a very young Clint Eastwood as a lab technician puzzling over the whereabouts of a white lab rat. At the conclusion, the Creature is again riddled with bullets—this time in the Florida Everglades, where he is apparently left for dead. It is there that he somehow survives, and is again stalked and found in a second and final sequel, The Creature Walks Among (1956). This installment was photographed “flat,” but its storyline takes an unusual twist and is perhaps the most inventive of the three Creaturefilms.

Replacing Jack Arnold at the helm was his protégé, John Sherwood; although virtually all of the other key participants of the two earlier films returned for this final outing. After the Gill Man is found, he’s accidentally burned during an attack on a boat. To save his life, the scientists who’ve come to capture him discover he has a pair of vestigial lungs, which they inflate, thus transforming him into a land animal. The true monster of the piece is not the man-fish, but is instead the driven and highly possessive Dr. William Barton (Jeff Morrow), the leader of the expedition. His lovely young wife, Marcia (Leigh Snowden) is the object of his possessiveness, and he is moved to murder when a hired hand, Jed Grant (Gregg Palmer), makes advances to her, which Barton wrongly assumes she has encouraged. Barton attempts to hide his crime by tossing Grant’s body into the Creature’s cage, but the Creature flies into a rage and breaks free. He kills Barton before returning to the sea; this time presumably to drown when he attempts to breathe underwater with his new lungs.

Of the three films, this final effort provides the most sympathetic portrayal of the aquatic anomaly, and also gives us a far more radical redesigning of the costume. As a reconstituted land animal, the creature is more massive and his facial features and hands are almost man-like. Playing the new and improved Gill Man is Don Megowan, with Ricou Browning again reprising the role in the scenes leading up to his accidental disfigurement and capture.

With the financial success of It Came from Outer Space and the encouraging buzz on Creature from the Black Lagoon as it made its preview rounds in the closing months of 1953, William Alland was quickly identified as a key player in the burgeoning field of science fiction movies. Always vigilant in his search for new properties, Alland took a meeting in the fall with Victor M. Orsatti, a former baseball player for the St. Louis Cardinals and later an influential Hollywood talent agent with a list of clients that included the likes of Frank Capra and Judy Garland. Orsatti, working with director Joseph Newman and writer George Callaghan, put together a proposal to make an epic space film based on the novel This Island Earth by Raymond F. Jones. With the obvious exceptions of George Pal’s Conquest of Space, which was concurrently in production at Paramount, and MGM’s Forbidden Planet, also in production at the time but released a year later, few if any of the SF films of the 1950s bore much resemblance to science fiction on the printed page.

Originally run as a series of connected stories in the SF pulp magazine, Thrilling Wonder Stories (in 1949 and 1950, later published in book form by Shasta in 1952) This Island Earth seemingly had everything one could want in an SF story—epic scope, original ideas, a compelling mystery, and an interplanetary war. To further enhance the project, Orsatti and Newman commissioned a Disney artist, Fransiscus vanLamsweerde, to create a series of illustrations designed to demonstrate the property’s visual potentials. With his involvement in This Island Earth, vanLamsweerde quit Disney to pursue a career in freelance illustration. Despite significant reservations about Callaghan’s script, Alland negotiated a deal to buy This Island Earth for production at Universal. Of the principals involved in the initial proposal, Newman was to be retained to direct, since Jack Arnold was otherwise occupied with production of the first of the Black Lagoon sequels, Revenge of the Creature .

Alland, a life-long science fiction fan, had been especially fond of the monsters devised by Westmore’s make-up department for his films, and felt that they were an integral part of what made them popular with movie audiences. He insisted that any re-writing of Callaghan’s script include, however incidental, a creature of some sort. Franklin Coen was assigned to prepare a new screenplay, but he initially balked at the idea of adding a monster. So, too, did actor Jeff Morrow, who was cast early on in the key role of Exeter, an alien scientist who has come to Earth on a secret mission. Recycling some of the discarded early design concepts of the Xenomorph from It Came from Outer Space, and borrowing heavily from Edd Cartier’s illustrations for Travelers of Space (1950), a copy of which they borrowed from the Universal reference library, Bud Westmore and Jack Kevan went to work on devising a costume for the Metaluna mutant, a seven-foot-tall synthetic humanoid insect bred by the inhabitants of the planet Metaluna to do menial work. To reduce the cost of producing the outfit, it was decided to dress the mutant in pants. Again, working the preliminary concept drawings, was Milicent Patrick, while Beau Hickman and John Kraus worked swiftly to realize maquettes of the designs in plastalina.

While the Gill Man of Creature from the Black Lagoon reputedly had taken some six months or more to develop, the Metaluna mutant literally came together in a matter of weeks, and cost only about half as much. Beginning just after the first of the year, by mid-January 1954 Westmore’s team had successfully completed the mutant design. Of all those involved in its creation, Jack Kevan appears to have been the principal contributor. Indeed, Kevan worked very much alone in the final stages of development to come up with a composite of earlier ideas that was both highly original and frighteningly effective.

This Island Earth begins with physicist Cal Meacham (Rex Reason) departing Washington D.C. by jet after a scientific conference. When he nears the airfield of his employer, Ryberg Electronics Corp. in Los Angeles, his plane inexplicablyloses power. As the jet plummets to almost certain doom, the plane is suddenly engulfed in a luminous green glow and is safely brought to a landing. Afterwards Meacham asks his lab assistant, Joe Wilson (Robert Nichols), if he saw anything unusual. Wilson acknowledges having seen the greenish glow. Meacham returns to his lab and resumes his research into transmuting energy from common elements, again to discover something unusual.

Since the experimental process requires the generation of extremely high voltage, condensers are regularly replaced when they burn out exceeding their maximum capacity. Joe Wilson explains that in the last replacement shipment, in place of the normally bulky condensers, were a few reddish glass beads. The beads, however, have enormous voltage capacity and are resistant to penetration, even when subjected to a diamond-tipped drill. Meacham asks Wilson to wire Supreme Supplies, their source for the condensers, to order more of the beads for testing. Soon, an unusual catalog is delivered to the lab from the same mysterious source—Unit 16, which the two assumed was a division of Supreme. Intrigued, Meacham asks Joe Wilson to order the parts for an Interocitor, a mysterious device featured in the catalog that uses sub-atomic particles for communication.

The two work diligently to construct the complex device from plans supplied in the shipment. When finished, a mysterious voice emanates from the machine. It is the voice of Exeter (Jeff Morrow), a fellow scientist eager to make contact with Meacham. Exeter invites Meacham to join him and others in a scientific research project designed to put an end to war. Exeter then instructs Meacham to place the catalog and assembly instructions on a table within sight of the device and the Interocitor emits a powerfully destructive beam that reduces the materials to ashes. Reacting to the violent display, Meacham disconnects the Interocitor from its power source and the device is almost instantly reduced to smoldering rubble.

Meacham decides to accept Exeter’s offer, and Joe Wilson drives him out to a fog-bound Ryberg Airfield in the small hours of the morning to rendezvous with a mysterious, pilotless plane. The plane eventually lands in a remote area of Georgia where Meacham is met by a colleague, Dr. Ruth Adams (Faith Domergue). Cal is certain that the two have met before, and perhaps had a brief flirtation, but Ruth at first denies any memory of this. Cal is puzzled by her response and believes she is hiding something. From the moment of his arrival, Cal is also suspicious of Exeter and several of his colleagues. Exeter’s second in command, Brack (Lance Fuller), seems especially ominous—Brack, Exeter, and certain others at the research facility are white-haired and have unusually high, oddly-shaped foreheads.

Cal, Ruth, and another colleague, Dr. Steve Carlson (Russell Johnson), eventually come to trust each other and reach the conclusion that something unsavory is afoot. Ruth explains to Cal that several of their scientist colleagues at the facility have been subjected to some sort of mind control device, hence her caution during their first meeting. They attempt to flee the complex, and Carlson nobly gives up his life while creating a diversion so that Cal and Ruth can escape. As the two commandeer a small airplane, they see Exeter’s facility explode in the distance. Unknown to them, a huge flying saucer rises from a hiding place in the Georgia countryside. Their plane is snatched from the skies by a greenish tractor beam that draws it upward into the hold of the giant spaceship.

On the ship, they are taken to Exeter, who explains that the spaceship is on its way to a planet called Metaluna in another galaxy. Exeter and his crew are native to this distant world, which is at war with Zahgon, a rogue planet that was once a comet. Exeter’s mission on Earth was to recruit human physicists to aid in the production of atomic energy from alternative fuel sources in order to support Metaluna’s ionization layer, a barrier that helps to shield the world from Zahgon’s attacks. Despite the protective ionization layer, however, Metaluna’s surface has been reduced to a barren wasteland and its people have taken refuge underground. The world has also lost most of its scientists in the war, and its force field is now close to failing.

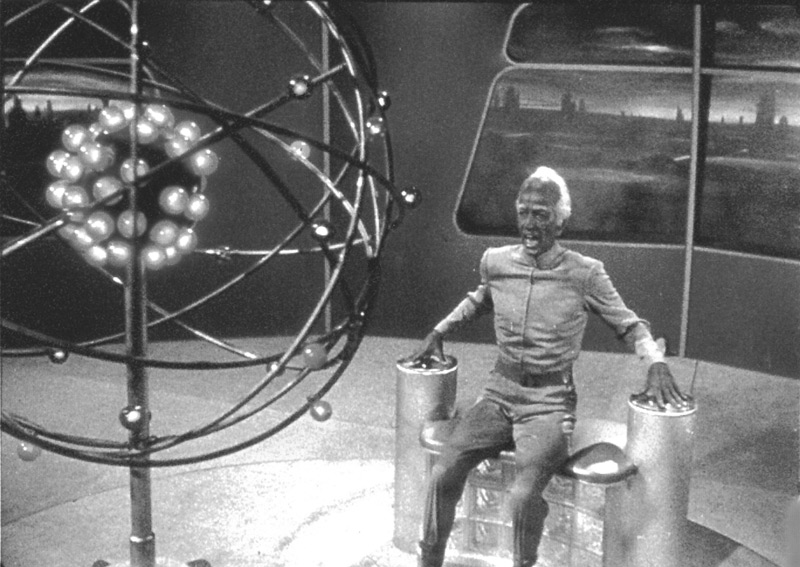

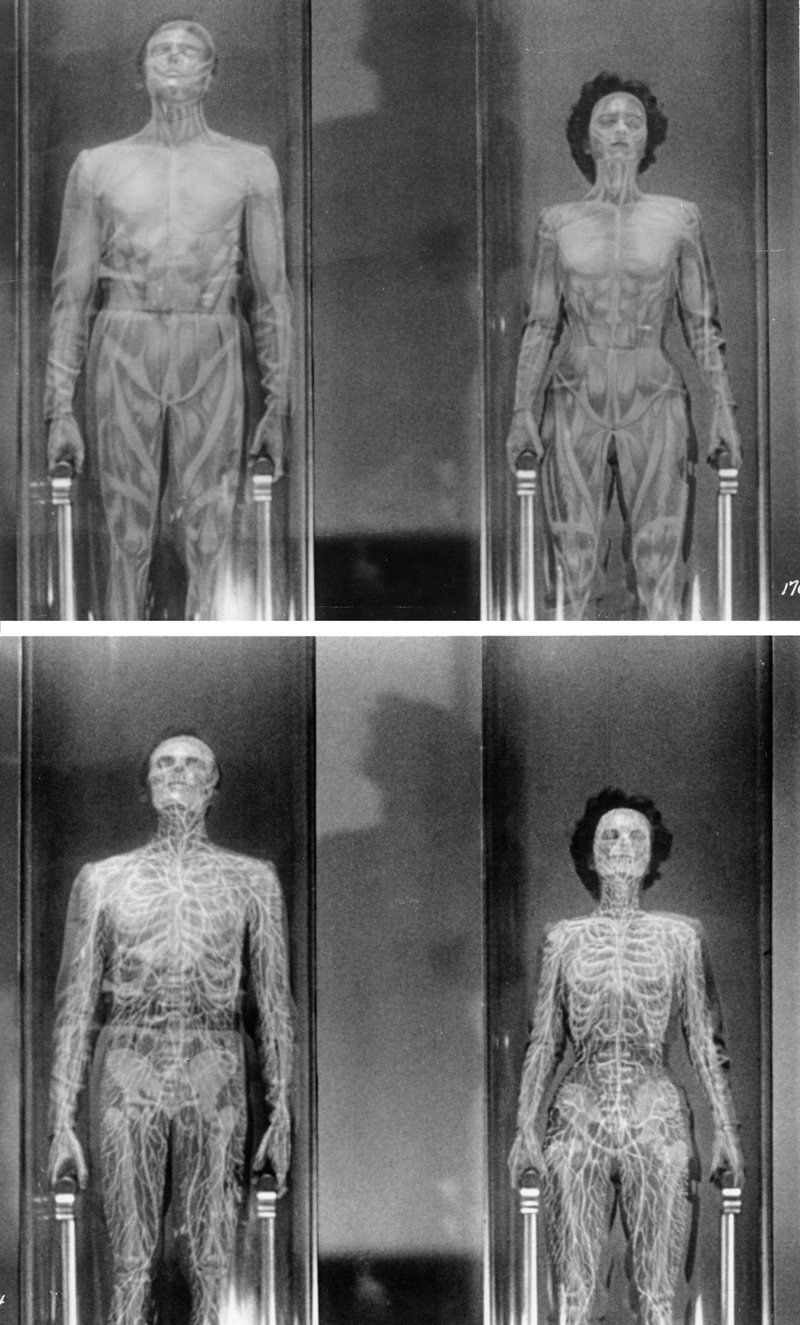

The Monitor (Douglas Spencer), the supreme leader of Metaluna’s government, has instructed Exeter to take Meacham and Ruth Adams to their planet where they are expected to continue their research. While en route, the two human scientists are subjected to the conversion tubes—cylinders that prepare their bodies for life on Metaluna where the atmospheric pressure is equal to that at the bottom of the Earth’s deepest oceans.

Their arrival on Metaluna is too late, however. In a meeting with the Monitor the humans are informed of a plan for the surviving Metalunans to re-locate to Earth, should the ionization layer ultimately fail. Cal and Ruth are appalled at the prospect of such an intrusion on their home world. Frustrated by the Earthlings, the Monitor orders Exeter to take them to the Thought Transference Chamber where they will be stripped of their free will. On the way to the chamber, Ruth, Meacham, and Exeter encounter a mutant. Exeter explains that, though fearsome in appearance, the creatures are usually docile. At that moment, a Zahgon attack destroys the Monitor’s Dome, killing the Monitor and the mutant in the process. Exeter persuades the two humans that he is willing to help them make their escape from the planet and they flee the rubble of the Monitor’s Structure, making their way to Exeter’s ship. When they arrive at the ship they find a wounded mutant standing guard. Exeter orders the creature to stand aside but it attacks him with its pincer-like claws. Cal comes to Exeter’s aid and they believe they have killed the mutant, but the wounded creature stumbles onboard just as the hatch is remotely secured and the ship takes off.

As they soar off into deep space Metaluna is heavily bombarded, transforming the planet into a newborn sun. While the three enter the conversion tubes, the injured mutant makes its way into the control room. The creature attacks Ruth but is finally destroyed by the change in atmospheric pressure. As they approach the Earth, it becomes evident that Exeter’s wounds will prove fatal without medical attention. Exeter refuses treatment, however, having come to the realization that he is truly alone in the universe without the companionship of beings of his own kind. He nobly speaks of wandering the universe in search of others like himself, but Meacham reminds him that he’s expended most of his ship’s energy returning them to Earth. Exeter, ignoring Cal’s observation, instructs Cal and Ruth to return home in their airplane. The plane drops from the cargo hold into the early morning sky as Exeter’s ship picks up speed and crashes into the sea, erupting into a ball of fire.

With the highly original and influential production designs of unit art director Richard H. Riedel and supervising art director Alexander Golitzen, This Island Earth proved to be a wellspring of innovation in virtually every aspect of its visual content. Riedel’s first notable production designs were for Rowland V. Lee’s 1939 Son of Frankenstein, the third installment in Universal’s saga of the Frankenstein monster. For it, Reidel produced striking, semi-abstract sets for the interiors of the Frankenstein Castle that reiterated and streamlined the look of the German expressionist horror films of the silent era. Significant visual elements from This Island Earth include, among many other things, animated sequences by Frank Tripper. The most ambitious of these is the highly effective transformation scene of Cal Meacham and Ruth Adams in the conversion tubes while en route to Metaluna. The effect was created by using chalk drawings on black card stock that were later colored and superimposed in an optical printer over still shots of actors Rex Reason and Faith Domergue as they stood in position on the flying saucer interior set.

The majority of the film’s highly complex space and battle sequences were supervised by special effects wizard David Stanley Horsley. Similar work of this extent and complexity would not be attempted again in a major American science fiction film until George Lucas’s Star Wars, some 22 years later, and then computers would make the difference in improving the process and making it somewhat easier. Horsley, though working on a fraction of Star Wars ‘s budget, was frequently reprimanded by the studio’s front office for cost over-runs, and walked off the picture when he insisted that Chesley Bonestell be hired to create the views of Metaluna from space using a series of matte paintings. At Bonestell’s then established rate of $1,600 per week, the management flatly refused. Horsley’s walk-out lasted six weeks before he set foot on the lot again. His contract with Universal was subsequently dropped, ending his nine-year involvement at the studio. Replacing Horsley for the completion of the special effects work was the film’s miniatures supervisor Charles Baker, a skillful and highly experienced technician who’d worked on This Island Earth from the start, and who was also a loyal, long-standing Universal employee. His special effects work at the studio dated back to the 1933 production of The Invisible Man. The distant views of Metaluna were finally achieved using the Universal globe, re-dressed in burlap and painted a golden-yellow color. Optical effects simulating the ionization layer were added to soften and enhance the image. The final result was quite convincing.

The film opened to favorable notices on June 1, 1955. By the mid-1950s, and in spite of their growing popularity, the major studios began to suspect that science fiction movies might be a passing fad. Some of this anxiety came, no doubt, from the strong connection that had been made between the horror and SF genres with the 3-D process. In the end, the process that so many had thought represented as much of a paradigm shift in picture-making as the advent of sound, was now viewed as something of a pariah. In a more realistic assessment of the situation, it wasn’t 3-D that had ruined these pictures; they were simply bad to begin with. The studios had, from the start, made an ill-considered habit of using the 3-D process as a bandage to patch any production in which they had little faith—and few of the majors truly understood, or had faith in, what it was that made science fiction stories work.

After the 3-D craze had come and gone, and as the cost of producing these films grew with the expensive and time-consuming need for more and better special effects, the major companies looked for ways to trim their budgets. At Universal, where monster movies had long been a staple, the answer seemed simple—concentrate on the monsters, keep the stories earthbound, and limit the hiring of cast and crew to contract employees. With the release of This Island Earth, and mainly from the standpoint of quality, Universal’s involvement in the SF genre had peaked.

In that same year, 1955, the studio released another interesting but far more conventional SF/horror movie in its giant bug opus, Tarantula. William Alland produced, Jack Arnold directed, and John Agar, who in the same year played the lead in Revenge of the Creature, starred. In the admittedly limited sub-genre of big bug movies, Tarantula, despite its flaws, is second in quality only to the first film of this kind, Warner Brothers’ highly successful science fiction thriller Them! While nature provided the creatures for these pictures, it was science—and more specifically, the atom—that created the mechanism to transform them from diminutive co-inhabitors of planet Earth into raging, life-threatening monsters.

As a contract producer for Universal-International during the 1950s, Alland continued to churn out a fair volume of programmers, mainly in the Western and science fiction genres. Following Tarantula ,he produced The Mole People (1956), directed by Virgil Vogel. This off-beat hybrid of SF and fantasy would be among the last of the Universal films with which Milicent Patrick’s name would be associated. Its titular creatures are notable for their imposing design, but they are almost incidental to its plot, which involves a lost tribe of ancient Sumerians who somehow come to reside in the Earth’s interior.

That same year, Alland produced the last of the Gill Man features, The Creature Walks Among Us . In 1957, his last year under contract to Universal, Alland produced a second big bug movie, The Deadly Mantis, and also an interesting if under-budgeted lost world film, The Land Unknown ; the latter about a subtropical oasis in the Antarctic inhabited by prehistoric monsters. These later efforts, mainly by virtue of their limited budgets, clearly reflect a diminished interest by the studio in the making of science fiction pictures.

Alland’s last two feature-length science fiction films, The Colossus of New York and The Space Children, were both released by Paramount in late June 1958. For The Colossus of New York, Alland worked with director Eugène Lourié, a former art director who frequently collaborated with French film director Jean Renoir. In the 1950s, the Russian-born Lourié branched into directing and became something of a specialist in giant monster movies (The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, 1953; The Giant Behemoth, 1959; Gorgo, 1961). The Space Children was Alland’s final feature film teaming with director Jack Arnold.

In 1959, Alland had his last formal involvement with science fiction as the producer of the short-lived syndicated TV series, World of Giants. In being the driving force behind the Creature trilogy, and for having produced the genre classics, It Came from Outer Space and This Island Earth, William Alland left an indelible mark on the cinema of science fiction. Surely, not one of these works is without its flaws. They were certainly not pure SF, in the literary sense, yet they defined the era of the Cold War through the metaphoric language of the fantastic in ways that many more conventional films could not, and they were wildly popular in their time. Alland retired from the movie business in the late 1960s, and died in 1997 at the age of 81.

For most of his long and highly active career, Jack Arnold maintained a reputation as an efficient journeyman director who consistently could bring films in on time and on budget. This common view of his work changed in 1970 with the publication of British film critic John Baxter’s landmark book, Science Fiction in the Cinema. In it Baxter proclaimed Arnold a genius, and referred to at least one of his films, The Incredible Shrinking Man, as a masterpiece. Baxter elaborates:

From 1953 to 1958, reaching across the boom years, Arnold directed for Universal a series of films which, for sheer virtuosity of style and clarity of vision, have few equals in the cinema. His dramatic use of the Gill Man, initially no more than a routine Universal “creature” designed by make-up genius Bud Westmore, has raised it to the pantheon of mythopoetic figures along with Dracula and the Frankenstein monster, and today his strikingly original conception of this beast/man has made it a central one in 20th century mythology. Adopting the pale grey style of SF film, he raised it briefly to the level of high art, bypassing the cumbersome attachments of 20 years’ misuse to tap again, as [James] Whale and [Earle C.] Kenton had done, the elemental power of the human subconscious. No imprint lingers so indelibly on the face of modern fantasy film as that of this obscure yet brilliant artist…Predictably, all Arnold’s films embody, in one form or another, the two basic preoccupations of SF film—the threat of knowledge and the loss of individuality, though his main interest is in the first, and the danger of technology when it is separated from human feelings. The Gill Man, like the afreet of Arabic legend, cannot be controlled after he has been conjured up and, as in most mythologies, only pure human responses like love can protect humanity from its power.

Following the 1955 release of Revenge of the Creature, Arnold focused for a time on a series of Westerns, not returning to SF again until 1957 when he went to work on what is perhaps his best film, The Incredible Shrinking Man. Based on his own novel, The Shrinking Man, author Richard Matheson adapted a compelling and literate script to the screen, fraught with existential ideas and great human pathos. In addition to hailing it as a masterpiece, Baxter describes the film as “a fantasy that for intelligence and sophistication has few equals. Written with Matheson’s usual insight, and directed with persuasive power, this film is the finest Arnold made, and arguably the peak of SF film in its long history.”

Substantially less satisfying is Arnold’s last SF film for Universal, Monster on the Campus, released in 1958. It was the second of two science fiction pictures he directed that year, the other being The Space Children for Paramount. The Space Children was his penultimate collaboration with producer William Alland. The following year he directed two segments of Alland’s syndicated TV series World of Giants. The show, starring Marshall Thompson as a miniaturized intelligence agent, was an attempt to utilize the giant props built by Universal for The Incredible Shrinking Man . Although he’d been directing television throughout his entire career, after 1975 Arnold concentrated his efforts more fully on the small screen. Among the great many shows he directed were episodes of Ellery Queen (1975), The Bionic Woman (1976), Wonder Woman (1976), Homes and Yo-Yo (1976), The Love Boat (1977), The Misadventures of Sheriff Lobo (1979), Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979), The Fall Guy (1981), and Beauty and the Beast (1987).

In early 1982, Arnold found himself back at Universal working on a proposed re-make of Creature from the Black Lagoon during the brief 3-D revival of the 1980s. Efforts to re-make the landmark film have surfaced regularly ever since, and following the commercially successful updating of the classic 1932 horror thriller, The Mummy (1999), a revisit to the Black Lagoon seems almost inevitable. That 1982 attempt eventually evolved into a second sequel to the popular shark thriller, Jaws (1975), resulting in the insipid Jaws 3-D (1983), directed by Joe Alves. At about the same time, Arnold attempted to interest the studio in a re-make of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, but after a great deal of preparation the project was finally dropped.

Journeyman director or not, there is little question of the importance of Jack Arnold’s role in the shaping of the modern science fiction film. In each of his genre pictures, there is a consciousness of the increasing influence that science has in our daily lives. Often the protagonist is the unwitting victim of some new development that has inexplicably gone out of control, giving us pause to think about the potential dangers of the new world that scientific advancement has wrought. Scott Carey of The Incredible Shrinking Man is a prime example of an Arnold Everyman; happily vacationing at sea and oblivious to the strange mist into which his boat is sailing. Thereafter he will never again be the same. He will lose his marriage, his worldly possessions, the very life in which he’s grown comfortable and presumably happy, yet he is determined to survive and to face whatever future awaits him. Despite a wariness of great and incomprehensible upheaval, there is also an abiding faith in the human spirit. Somehow, Man and his world, however altered, will endure. Arnold passed away at the age of 76 in 1992, but the message of his films prevails as a cornerstone of contemporary science fiction cinema.

The ambitious Bud Westmore remained active throughout his life, receiving screen credit for his make-up work on more than 400 films. In 1937, at the age of 19, he married the noted comedic actress Martha Raye. The marriage lasted less than three months. He later re-married to actress Rosemary Lane, one of the talented Lane Sisters (that included Lola and Priscilla), but that union, too, ended in divorce. Intermittently, while working on feature films, he did quite a bit of work for television, including supervising the make-up for The Munsters and for Rod Serling’s Night Gallery (1964-’66 and 1970-’72, respectively). His last film was Soylent Green, released around the time of his death in June 1973. Westmore was 55.

Of the superbly talented Jack Kevan very little is really known. After the SF boom went bust in the late 1950s, he seems to have departed Universal and struck out on his own. In 1959 he produced The Monster of Piedras Blancas, an interesting, low-budget independent picture for which he also conceived the story and created the title monster. It has an unequivocal kinship to Creature from the Black Lagoon for Kevan used many of the original Universal make-up department molds to fabricate the costume. The film marked the beginning of his association with director Irvin Berwick. Kevan later collaborated with Berwick in co-authoring the script for the crime drama The Seventh Commandment (1960), then contributed the story to Berwick’s The Street is My Beat, in 1966.

Universal made other SF films beyond those produced by Alland and directed by Arnold. One of the most interesting is Howard Christie’s production of The Monolith Monsters (1957), for which Jack Arnold contributed the story in collaboration with Robert M. Fresco. This film takes a truly unique spin on the alien invasion theme, and presents undoubtedly the cinema’s most novel alien menace—huge crystals that can turn people to stone and can crush buildings as they topple to the ground under their own weight.

As to the elusive Milicent Patrick, the facts of her story lie tantalizingly out of reach. Film historian Tom Weaver believes that Ms. Patrick passed away sometime in the late 1970s, but some sources suggest otherwise. To address this matter I made inquiries with several knowledgeable people, including SF movie fans and collectors Gail and Ray Orwig. They produce a monthly publication about vintage horror and SF movies called The Big Eye Newsletter from their home and museum in Richmond, California. They responded with the following: “We checked with Harris Lentz and with the Classic Images obituary pages and have found nothing on birth or death dates… We have also found that she dated [character actor] George Tobias on and off for 40 years until his death in 1980. This puts the ’70’s death date from Weaver in doubt. She married and divorced twice, and always seemed to come back to George Tobias.”

To further cast doubt on Weaver’s speculation is a January 1, 1986 page one interview with Milicent Patrick in The Los Angeles Times regarding her father’s role in the building of the Hearst Castle. Movie screenwriter David J. Schow has been a life-long Creature fan and is the editor and publisher of a uniquely specialized newsletter, The Black Lagoon Bugle. Schow has also worked as a consultant on several of the proposed Creature from the Black Lagoon re-makes since the early 1980s. He writes about Milicent Patrick’s transition to screen acting by stating, “She turned to modeling because of ‘headaches,’ and subsequently captured a flotilla of modeling prizes, as well as doing filmed and live-broadcast commercials. While appearing as ‘Miss Contour’ at the Ambassador Hotel [sometime in the late 1940s], producer William Hawks spotted her waiting for a bus and immediately steered her career toward motion pictures.”

Her film appearances began in 1948 with the Howard Hawks comedy A Song is Born, and include such landmark motion pictures as The Kentuckian with Burt Lancaster, Lust for Life (1956) with Kirk Douglas, and Raintree County (1957) with Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor. Her last screen appearance was in the 1968 James Garner film, The Pink Jungle.

I received a detailed e-mail message about Milicent Patrick from David Schow on November 6, 2002. In it he writes:

Because of her involvement with Universal monster movies, particularly Creature from the Black Lagoon, I think fans have overcompensated by wrongly crediting her as a designer when her job was more ‘realization’—that is, visualizations of designs that were the result of group consensus…Bud Westmore was the gang boss of the make-up department at Universal, just as his brothers Perc and Mont were the head honchos at Warner Brothers and MGM, respectively. That initial group of five Westmore sons [Perc, Mont, Wally, Bud, and Ern], plus George, their father, was fiercely competitive, and no love was lost between them. Bud, in fact, replaced his brother Wally at Universal (Wally had done the Hyde appliances seen in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—masks subsequently taken on the road by Milicent Patrick)…I mention this only as preamble to the widely accepted notion that Milicent was not only denied credit for her design work on Creature and other films, but in fact got steam-rollered out of the industry entirely at the behest of Bud Westmore.

…Tom Weaver has previously noted Bud Westmore’s propensity to rush into the make-up shop whenever photographers were around, grab a tool, and pose in his natty street duds while his technicians are smocked and lathered in paint and latex. But Bud Westmore was the head of the department; I’m sure he saw that as his privilege, and any publicity was vitally important to each of the Westmores. According to Frank Westmore in [his book] The Westmores of Hollywood [by Frank Westmore and Muriel Davidson, Lippincott, 1976], Bud was ‘arrogant, power-driven, and rough on his employees…Young Tom Case was one of his victims. Tom was almost a Westmore, because he married the sister of Monte, Jr’s wife, yet after three years of working with Bud, Tom couldn’t stand his caustic attitude and quit—at the height of the Creature triumphs…’

…[the designing of the Creature] was obviously a group effort that included Jack Arnold (with his notion of re-designing the Creature head after the streamlined form of an Academy Award). From Bud’s perspective, he (Bud) “saved” the floundering design with four months of tweaks…Except that Chris Mueller sculpted the head and hands. I can’t account for Milicent’s mysterious invisibility—she continued to act in movies through 1968—except to suggest that she was so burned by the Westmore incident, or, possibly, blackballed outright, that she kept a determinedly low profile from then on.

Robert Skotak is a well-known SF movie fan, writer, and film historian, and is also one of Hollywood’s foremost special effects artists. He and his brother Dennis have created special effects for such films as Strange Invaders (1983), Aliens (1986), The Abyss (1989), Terminator 2 (1991), Batman Returns (1992), and Titanic (1997). Although the Skotak brothers are enormously versatile and work in such far ranging areas as production design, cinematography and make-up and special effects supervision, their forte is in merging digital media with highly detailed miniatures. Skotak interviewed Milicent Patrick several times over the years, still retains a fragile copy of her original resumé, and knew her to be suffering from a long illness.

Skotak contracted mononucleosis in 1977, around the time of his first meeting with Patrick, and the two commiserated about their difficulties in dealing with similar symptoms. He states, “I had a relapse in 1984, or thereabouts, and she and I compared ‘notes’ then, as well as a few years later…when she mentioned she was still feeling ill. It never left her, it seems.” Skotak said that during their final meeting she seemed weak. “When I first met her, ” he notes, “she was vibrant and seemed very young. She had a high energy level and was a very strong person.”

In a conversation I had with Skotak by telephone on November 8, 2002, he recalled clipping Patrick’s obituary, but was unable to find it for our interview. Although he could not be completely certain, he thought that he had seen her last in 1989, and that she might have passed away in 1995 or ’96. My efforts to track down that obituary have yet to prove fruitful.

When asked about her reaction to the Westmore flap, Skotak replied:

She went out on the road and explained it like it was. She credited Bud Westmore at every opportunity. What was happening was that she was a very bright, very attractive woman—very, very charismatic. People wanted to attach everything to her just by osmosis because she was there. It wasn’t her fault, and I know she didn’t intend that to happen. She was aware there was some kind of political problem between her and Westmore, but I don’t think she ever saw those memos [which took issue with her going out on tour]…She was always gracious and apologetic about stepping on anybody’s toes. She understood that some kind of flap had occurred, but I don’t think she ever knew the precise details. She was well aware that she was abruptly no longer involved with those films. She was very diplomatic in the way she handled it. But she was not bitter at all.

This Island Earth was just getting into the sketching stage when this whole Creature flap started. I’ve seen her early designs for the costumes [for that film]—they were very different from what they ended up with. I thought her ideas were colorful, very ‘character’ oriented and science fiction-y, but the rather simple costumes they wound up using probably made a lot more sense in terms of where the script wound up. They were cool in a very fun, science fiction way. Her drawings, in fact, were based on the first draft, which was more overtly ‘pulpy’ in feel. The ‘character’ quality, I think, arose from the fact that she was an actress and thought in those terms. (Her This Island Earth sketches, incidentally, were also make-up sketches showing what the Metalunans might look like.) Her work was mainly done in ink with white highlights.

She was a real stylist, I would say. She definitely had a way with line, and could really knock the stuff out fast. I think she took a lot of disparate ideas and some of the possibilities and composited them and helped steer the design in a cohesive direction—at least that’s what I got from her—which is why she would not take credit for all the design elements. That was her unique ability—as much as I could glean from her. She was key to the process, but I’m not too terribly sure of just what her contributions were in terms of the details of [the Gill Man]. She seemed to think the idea of the tail (once part of the design) just wasn’t ‘right,’ for instance.

“I know that Beau Hickman talked about the way they made the stipple on the suit by transferring an impression from the textured surface of a suitcase to create the pattern on the scales. He came up with the idea, but confessed that Kevan really did all the work; came up with all the stuff in the lab—i.e., not Westmore. Westmore was a great promoter who got the lab more work and money than might otherwise have been the case. But it went back and forth in a collaborative effort.

Milicent seemed to recall William Alland as being involved in the Creature design quite a bit. She liked him; thought he had a ‘thing’ about creatures…

Regarding the impact of her situation with Westmore on her career, Skotak added, “I don’t think she was ‘burned’…that was not her character, and the incident itself wasn’t quite that extreme…She was reaching an age where parts were harder to come by, didn’t want to go back to animation, and didn’t have the connections to make-up and costuming she had earlier in her career. It happens that way…”

So, then, there it is, a Hollywood mystery in the purest, most melodramatic sense; rife with tantalizing details, yet bereft of concrete, verifiable facts—all innuendo and hearsay, offering the vague details of what might have been a promising career, fallen victim to an ego out of control. As a mystery woman, Milicent Patrick cuts an alluring and romantic figure. As I searched libraries and internet obituary services in search of some definitive word of her passing, I half hoped that I would be unsuccessful in my quest. I have no reason whatever to question Robert Skotak’s memory of Milicent Patrick’s passing, yet the mere fact that I cannot lay hands on her published obituary is further evidence of her elusive nature, as though she had been conjured up by wishful thinking—a beauty who created a beast—and, in the end, never really existed.

Vincent di Fate is a science fiction/fantasy artist who’s work spans decades. He has been heralded as “one of the top illustrators of science fiction” by People and has several mantles full of Lifetime Achievement awards from the SFF community.